Thanks to the Hubble Space Telescope, we now know that a day on Uranus lasts for 28 seconds longer than previously thought – a difference that could be crucial in planning future missions to the gas giant

By James Woodford

8 April 2025

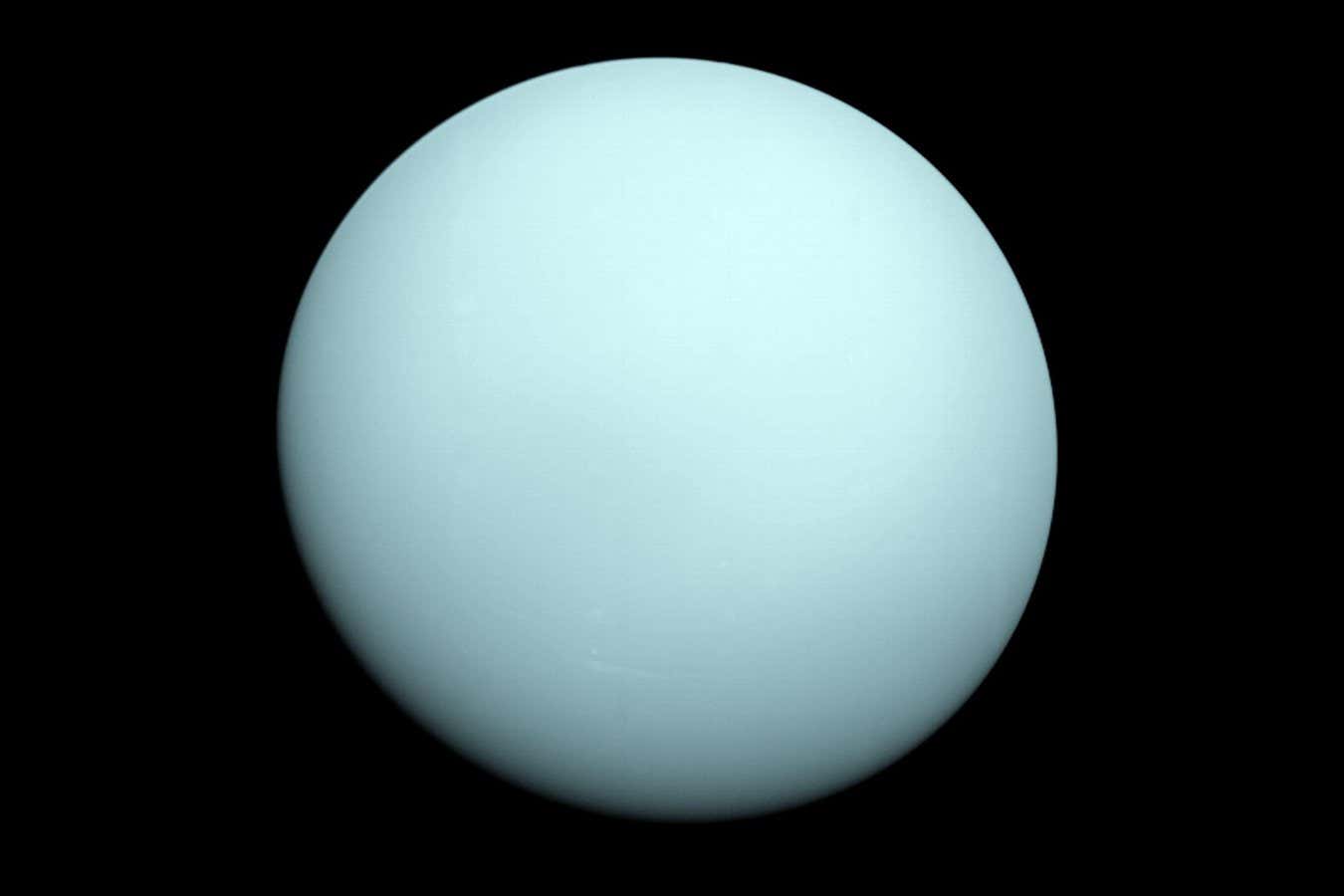

Uranus as seen by the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1986

NASA/JPL-Caltech

A day on Uranus just got slightly longer, thanks to more accurate measurements of its rotation period that should help scientists plan missions to probe the gas giant.

Figuring out the rotation period of the solar system’s giant planets is much harder than for the likes of Mars and Earth because ferocious wind storms make direct measurements impossible.

Read more

Dozens of stars show signs of hosting advanced alien civilisations

Advertisement

The first measurement of Uranus’s rotation came from the Voyager 2 probe, which made its closest approach on 24 January 1986. Researchers at the time determined that the planet’s magnetic field was offset by 59 degrees from celestial north, while its rotation axis was 98 degrees offset.

These extreme offsets mean that Uranus effectively rotates “lying down” compared with Earth, while its magnetic poles trace a large circle as the planet rotates. By measuring both the planet’s magnetic field and radio emissions from aurora at its magnetic poles, researchers at the time found that Uranus was completing a full rotation every 17 hours, 14 minutes, 24 seconds, with a margin of error of plus or minus 36 seconds.

Now, Laurent Lamy at the Paris Observatory in France and his colleagues have measured it to be 28 seconds longer. More importantly, their measurement is 1000 times more accurate, reducing the margin of error to a fraction of a second.